By Shauna Pomerantz, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON.

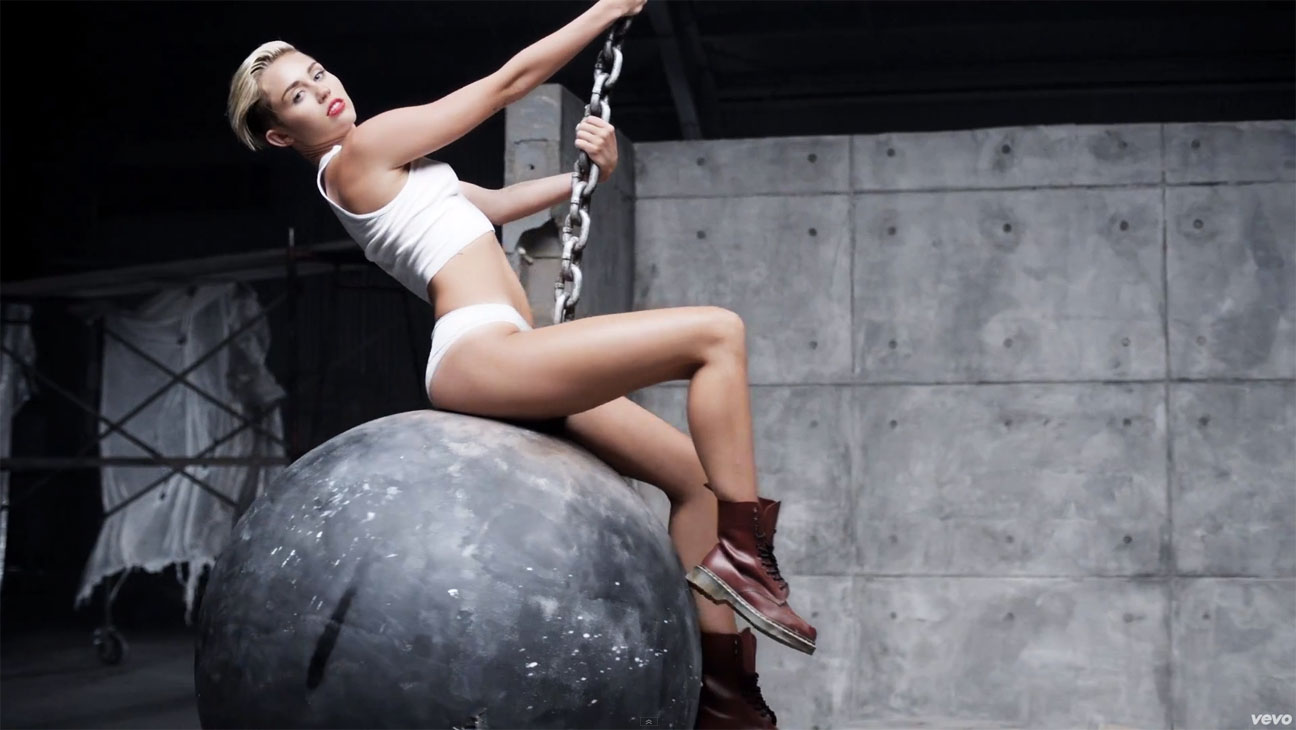

Now that the dust has settled on one of the most publicized popular culture controversies in recent history, it is time to reflect on what Miley Cyrus has done for feminism. Yes, I said feminism. The debates surrounding Miley’s infamous Video Music Award (VMA) performance and her subsequent Wrecking Ball video have left me feeling surprisingly optimistic about the future of feminism. And for this reason alone, I am grateful to the twenty-one-year-old for her provocative style, sound, and sexual display. More than any other female pop star—more than Britney Spears, Christina Aguilera, Katy Perry, Beyoncé, Pink, and even Madonna—Miley brought feminism to the public fore. Here’s why: by controversially performing young, white, pop star femininity, she ignited a conversation that still has people discussing what it means to be a young woman in the 21st century. And perhaps most surprisingly, this conversation has been multifaceted and intellectually engaged. I have been riveted by the various strands of these arguments, from aging pop stars to punk bloggers, media pundits to feminist academics, and young girl fans to male hipsters—all of whom have something interesting to say about not just Miley’s performance of femininity, but also what power can or might mean for girls and women at this time and place in history.

Never before has there been so much talk, text, and tweeting about feminist issues: gender performativity, empowerment versus oppression, misogyny in the music industry, sexual agency, slut shaming, racism and racialization, and why women receive so much criticism in popular culture when men receive almost none. What matters most in these debates is not who has the definitive perspective—the piece that decides if Miley is “good” or “bad” once and for all—but rather the sheer volume of discussion about young womanhood, sexuality, and power. Acting as a lightening rod, Miley provided people with an outlet for expressing feminist views about things that truly matter in our global capitalist, socially networked, celebrity obsessed culture. And each opinion continues to broaden previous statements—constantly re-shaping the discourse, but thankfully never quite nailing it down.

Take, for example, Sinead O’Conner’s powerfully worded “maternal” letter to Miley, suggesting that the music industry is pimping her out. She writes to Miley:

“The music business doesn’t give a shit about you, or any of us. They will prostitute you for all you are worth, and cleverly make you think it’s what YOU wanted …”

This intense warning of exploitation then ignited discussion on a number important feminist questions: What does it mean to be oppressed or empowered in the music industry? What about agency and sexuality? Who is in control? Is sexual empowerment “real” power? Under global capitalism, do human beings even count? In response to Sinead’s doom and gloom came a treatise on individualism and freedom of expression from Amanda Palmer. She writes to Sinead,

“Miley is, from what I can gather, in charge of her own show. She’s writing the plot and signing the checks, and although I think it’s tempting to imagine her in the boardroom of label assholes and management, I don’t think any of them masterminded her current plan to be a raging, naked, twerking sexpot. I think that’s All Miley All The Way.”

Then, in response to these two polemic pieces came Lisa Wade’s more academic effort to show how both Sinead and Amanda were equal parts right and wrong.

“On the one hand, women are making individual choices. They are not complete dupes of the system. They are architects of their own lives. On the other hand, those individual choices are being made within a system.”

And most recently, Laurie Penny made the exquisitely elegant case that we have turned Miley into a gruesome symbol for all girls, doing grave violence to the multitudes of girls out there who live brave and fabulous lives.

“In the real world, girls are not all the same. Attempting to make any one woman stand in for all women everywhere is demeaning to every woman anywhere. It tells us that we are all alike, that for all society’s fascination with our feelings and fragility we are considered of a kind, replaceable. We’re all the same, and we’re all supposed to have the same problems. And that’s the problem.”

And the conversation just keeps on exploding. So suddenly, it does not matter to me whether Miley has done something “right” or “wrong”. I no longer care if she is “good” or “bad” for girls. All that matters is that for this glorious period in time, it seems as though the entire western world is talking about feminism. And the feminism under discussion is never just one kind, but always multiple and diverse. It is intersectional (at times focusing on race, gender, class, and sexuality); it is academic (at times focusing on identity, power, and agency); it is everyday (at times focusing on raw emotion and opinion); it is everyone (and anyone with a keyboard and an Internet connection); and it is everywhere (emerging at work and parties between people of all ages and cultures).

No matter what you may think of Miley, her videos, or her media image, there is no denying that she has done something truly important for feminism. She made it a household word, a water cooler topic. She incited an impassioned and textured conversation about feminism; she proved that feminism is still relevant and necessary; and she exemplified the powerful and contradictory possibilities both young womanhood and feminism hold. So thank you for bringing feminism back, Miley. Maybe it never really left, but it has certainly been driven underground in the popular realm for quite some time. Denied, faded, and deemed a “dirty” word, thank you for helping to illuminate feminism in the floodlights of public discourse.